Resurrecting The Past

The Faro Mine Remediation Project is one of the most complex abandoned mine cleanup projects in Canada. Opened in 1969, it was the largest open pit lead-zinc mine in the world, at one time. It was abandoned in 1998. The remediation project was established to prevent contamination of the surrounding water and land from the former mining operation.

The Faro project is complex because of the mine’s remote location, about 360km (a 4.5-hour drive) north of Whitehorse, YT. Further, the site covers 25 square kilometres – about the size of Victoria, BC – and contains 70 million tonnes of tailings and an additional 320 million tonnes of waste rock, bringing the obvious attendant risks to human and environmental health. The project is similar in magnitude to the Giant Mine in the Northwest Territories, which closed in 1999.

Marie-Pascale Rousseau, a Royal Military College graduate and civil engineer, is the Director of the Faro Mine Remediation Project for Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC). Rousseau explains that the project is funded by the Government of Canada’s Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. CIRNAC leads the care and maintenance, site monitoring, consultation, urgent works and future remediation plan design.

Canada is committed to meaningful engagement with the affected Indigenous communities on all aspects of the project, from site remediation planning to managing the project for maximum socio economic opportunities and benefits to local Indigenous communities. Three Indigenous communities in Yukon are affected by the site; the mine complex is located on the traditional territory of the Kaska, including the Ross River Dena Council and Liard First Nation, and it is upstream of the Selkirk First Nation.

Project stakeholders include the Town of Faro, the Government of Yukon, the Yukon Conservation Society, and the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board. Other federal entities, such as the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans and Environment and Climate Change Canada, also have a stake in the outcome of the project.

When the mine opened in 1969, the regulatory regime was not as robust as it is today regarding the environmental and socio economic impacts of such projects or the requirements for companies to set aside securities for future remediation work. As a result, when the site was abandoned in 1998, the clean-up became the responsibility of the territorial and federal governments. The Faro site had been placed in receivership; care and maintenance of the site became the responsibility of the Yukon government in 2009 and was transferred to the federal government in 2018.

The remediation process begins with ensuring the site’s safety, stability and security to the extent possible, in its current state. The project proceeds through consultation and permitting processes before formal remediation begins. Ongoing environmental monitoring ensures that systems are working as they were designed, so that the site remains compliant with environmental health and safety regulations. CIRNAC manages all related agreements and contracts.

The complexity of the project is reflected in the remediation plan’s over fourteen-thousand-page length. It is currently under review by the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB), an independent arms-length body.

While the plan is being assessed, necessary construction and infrastructure upgrades and urgent works are being undertaken. In addition to civil engineers maintaining site infrastructure such as roads, buildings, dams and stream channels, there is a larger group of environmental engineers, biologists and other environmental professionals involved in the project.

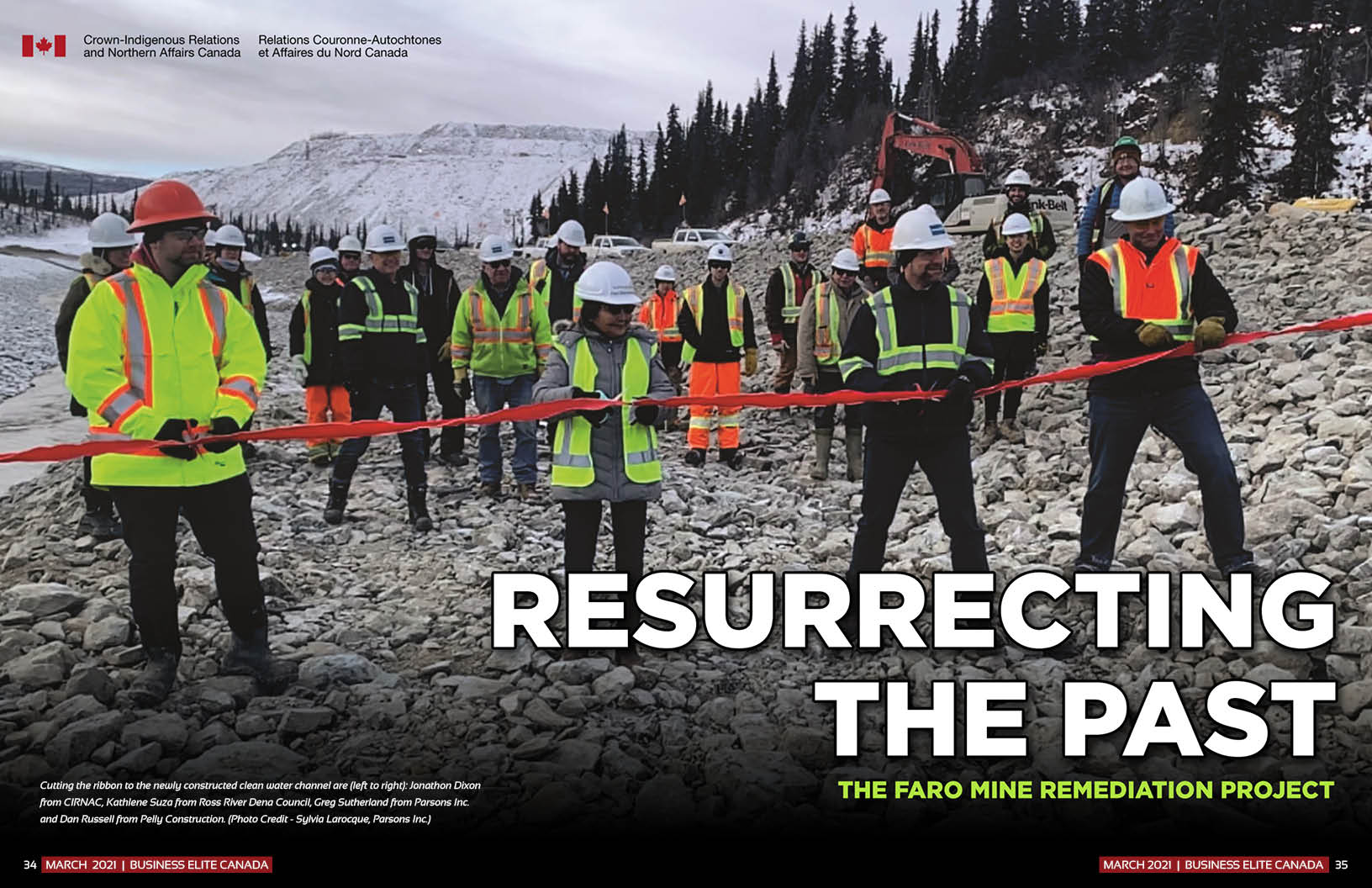

Among other things, these team members monitor water quality through hundreds of data points every month, ensuring contaminated water is collected and treated before it leaves the site, meeting all environmental standards. For example, the North Fork of Rose Creek realignment has been a major civil construction project with a goal of preventing the creek from coming into contact with contaminated water on the site, thereby mitigating the impact on fish and wildlife. Additional construction will begin on the down valley surface and groundwater interception system late this winter.

Over the next three to five years, the remediation plan assessment will be completed, a water license application will be submitted, all regulatory authorizations will be issued, and a construction manager will be hired for the site. The formal remediation period is expected to begin in 2025/26 and last about 15 years, which would see the project conclude in 2040. A further 20 to 25 years of testing and monitoring will follow, though the mine complex will always remain under active management and monitoring.

Since the mine is situated on Kaska traditional territory, the goal is to make the environment as safe and available as possible to First Nations for hunting and other traditional uses. For every construction project in the remediation process, an Indigenous Opportunity Considerations plan makes it incumbent on contractors to hire and/or train local Indigenous workers. That stable work and the resulting economic benefit contributes directly to the health of the First Nations communities involved.

As an example, one contractor partnered with the Yukon University’s Centre for Northern Innovation and Mining and the University of Alaska to design a three-week heavy equipment operator training program for local First Nations members.Per Rousseau, “We want meaningful engagement with the affected Indigenous communities on all aspects of our project. We are on traditional land; we have to be very mindful of that. They have a say in the site remediation plan, and we’re trying to maximize socioeconomic opportunities for them and provide benefits to local First Nations. We very much want them to benefit from the work that we’re doing on site.”