Rethinking Urban Planning in Vancouver

By Rajitha Sivakumaran

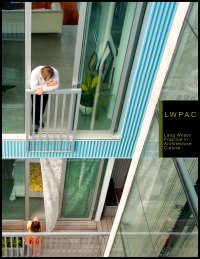

Architecture culture refers to something beyond the building. This philosophy converges on thoughts about how we live in cities and how we interact with each other. “Our buildings are a platform where our everyday culture can unfold,” said Oliver Lang, principal at the Vancouver-based Lang Wilson Practice in Architecture Culture (LWPAC). This fixation with architecture culture is why this firm is slowly transforming urban planning in Vancouver. Lang and his team have tasked themselves with the ambition of creating buildings that empower people by serving as places of interaction and engagement.

Having worked in Berlin and New York City, and formerly employed as a professor in architecture design, Lang began LWPAC in 1998. The firm focuses mainly on architectural design, but is also involved in research and development, and prototyping. The firm has always used a multidisciplinary approach to architecture, incorporating design, technology, materiality and sustainability within the larger urban ecosystem. Operating under the name Intelligent City, Lang works on fabrication and real estate development as well.

The firm’s first project involved a university building in Chile. Completed in the year 2000, this building won a number of awards and was recognized on a global scale, which gave LWPAC the attention it needed to spring high from its humble beginnings. The project’s success has also fuelled the initiative to rethink urban housing and planning in Vancouver.

The complexities of urban planning

The urban environment is often associated with increasing density due to an imbalance between sky high commercial towers and low-rise sprawl. Cities draw commercial corridors, which contribute to clusters of towers and people living within these cities are drawn to individual houses, which adds to urban sprawl. Virtually nonexistent in this picture is what Lang and others termed ‘the missing middle’.

The solution LWPAC has devised is a middle ground that gives people the same livability of a house but in a vertical arrangement. The product of this innovative philosophy was the ROAR_one project, a mixed-use building that incorporates commercial space and multiple stacked houses. Built to resemble individual houses, these double-storey units coexist in an interlocking way.

Historically, there are many good examples of this middle ground in a number of classical European cities. In Barcelona, for example, buildings are consistently eight or nine stories tall. In Paris, medium-density habitation blocks encircling a courtyard have worked well to offer a space for both living and communal interaction. Other places have used an integrated design that combines housing with commercial spaces. Vancouver is home to a few similar models, like the Olympic Village, which was built up to a height of eight stories with many functions integrated into the space. However, the tendency is to fall towards towers or individual homes, Lang said.

The ROAR_one project is a reference project from a sustainability point of view too, being a model of the Green City concept, which aims to reduce the carbon footprint of a building. Passive Haus is a similar concept followed by LWPAC; it refers to a residential model that reduces energy needs, such as using solar energy for heating during the winter. Lang is a strong advocate of the Living Building Challenge, which incorporates all other ecological matters associated with architecture, from water usage to the lifecycle of materials used in buildings.

The Monad project was launched based on these standards and generated much recognition and a number of awards due to its ability to incorporate both sustainability and affordability. LWPAC was also one of the 2016 winners of the Urban Design Award, presented by the City of Vancouver, for their involvement with the Vanglo House. Currently working with the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, the firm will continue to embed these standards in all of its projects.

“I think we’re missing a range of models and technologies that can be used to build future cities, and we need to aim for that,” Lang said. By this Lang refers to the incorporation of intelligent urban infrastructure, like bike lanes and public transportation, to get people out of cars and bring them closer together. Proximity is an important part of the Green City concept; increased accessibility to commercial enterprises and workplaces will help the entire city go green.

Impediments to innovative planning

Vancouver is expected to grow by two million people in the next 30 years and according to Lang, a singular approach to construction will not be able to accommodate this immense growth. The focus needs to shift away from the interest of developers, who are centred on short-term goals, to people and design.

Innovation is the key to a perpetually thriving city; it is also something that is not readily embraced. “We build our cities with models that are typically very repetitive,” Lang said. Instead of repetition, Lang’s firm would like to introduce adaptability, choice and a shift away from a buyer-investor focus in the real estate market to visibility, affordability and quality.

In Lang’s line of work, the biggest challenge he faces every day is regulation, which tends to limit innovation. “Municipalities often work with very outdated regulatory frameworks and bylaws that are 20 or 30 years old,” said Lang. LWPAC is carrying out dialogues with the municipalities that it works with to communicate the importance of change and the role it plays in driving innovation forward.

“The innovation and drive to renew our city is not sufficient, but I think that is changing,” Lang said.

Another hindrance to innovation is an adversity to risk. “It’s a bigger risk not to change the way how we do things than keep doing what’s status quo,” Lang said. The greatest risk, in his opinion, is resistance to innovation. “That’s why we created a firm where we can drive innovation ourselves,” he added.

The third point Lang sees as an impediment to urban design is the segregation between engineering and construction. He believes that these proponents of a project must be integrated from the very beginning in order to successfully rethink urban planning in Vancouver.

“For the city of Vancouver, we have the potential to make this a phenomenal place. Our goal is to drive forward a deep integration between all aspects of design and that’s from the cultural, to the way that we live in the city to the technological. We’ll keep driving that forward,” Lang said.

www.lwpac.net